“Liberty Monument”

Wallace and Cornwall Kirkpatrick, Anna Pottery, Anna, Illinois; 1873

Stoneware (molded and hand-modeled)

Winterthur museum purchase 2021.0017

Who should be involved in interpreting the themes of privilege and inequality portrayed by an object like this one?

In 2021, Winterthur acquired this unique and previously unknown ceramic masterwork. In part, it portrays the Colfax Massacre, a racially motivated event in Louisiana in 1873 that is largely ignored in mainstream history books. Winterthur alone cannot interpret and share the important story depicted by the Monument. Having collected with an eye to diversity and inclusion for decades, Winterthur is working to create a multi-vocal interpretation for this object by engaging with community members, scholars, students, and other stakeholders. The interpretation of this complex object will evolve over time. Join us in this conversation about America’s material past.

Is violence and conflict over voter suppression new?

White potters Wallace and Cornwall Kirkpatrick, the white potters who made this piece, placed Lady Liberty atop the sculpture. Liberty ironically bears witness to the massacre of as many as 150 Black citizens of Colfax, Louisiana, who protested voter suppression relating to the state’s 1872 gubernatorial election. News of this atrocity spread quickly across the country via newspapers and word of mouth, offering differing “facts” about the massacre. We are unsure which version of the news reached the Kirkpatricks in Illinois, but their visceral response to the event is clearly shown here.

Where has this object been for roughly 150 years . . . and why was it preserved?

For their booths at local fairs, the Kirkpatricks created large, eye-catching centerpieces to draw in potential buyers for their pottery company’s typical utilitarian wares. Was this work created for that purpose?

Created in 1873 in Anna, Illinois, the “Liberty Monument” was discovered in 2021 near Boise, Idaho. No history survives of its ownership nor its voyage of more than 1,700 miles to the West from Illinois.

Lady Liberty, who originally may have been holding scales, surmounts the Monument. A Black woman scales the tower towards a ballot box marked “Kellog, [sic]” representing William Pitt Kellogg, the 1872 gubernatorial candidate favored by Black voters.

Can an object simultaneously show support for an underrepresented group and disparage those same people?

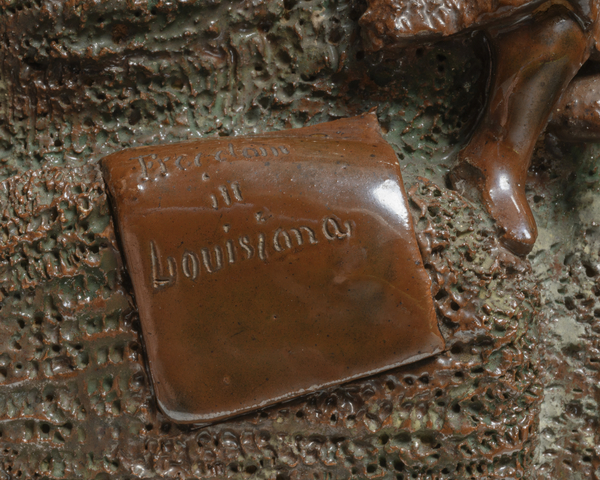

The Kirkpatricks were known for their strong, public criticism of government corruption and social inequality. On this object, sarcastic inscriptions— “Our protection / under the / Civil-right / Bill,” a reference to the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that provided U.S. citizens of all races equal protection under the law, and “Freedom / in / Louisiana”— are placed near the portrayal of the Colfax Massacre. Although sympathetic to the plight of the Black victims of the attack, the brothers used then-common racist stereotypes when modeling of the figures.

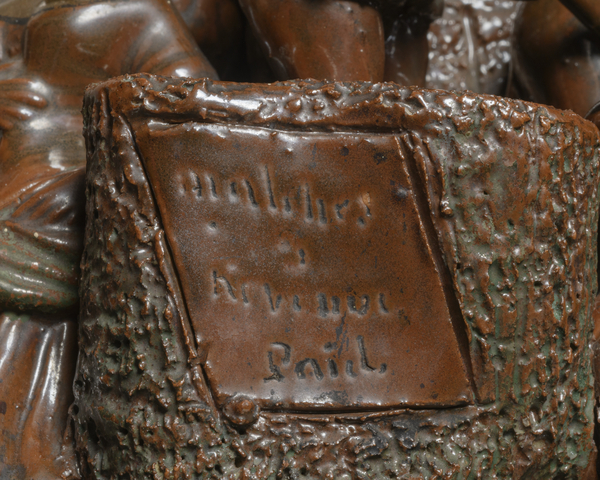

The four match safes (the large hollow wells) indicate the Monument may also have been displayed in a place of business such as a tavern or bar. Nearby inscriptions point to the irony and inequity of a tax placed on matches as part of the Revenue Act of 1862, which was designed to help fund the Civil War. Related inscriptions read: “U.S. revenue / on matches / 3 cents”, “no tax on silks / and Jewelry / put i[t] all on / matches”, “matches / revenue / Paid”, “matches / 3 / cents.”

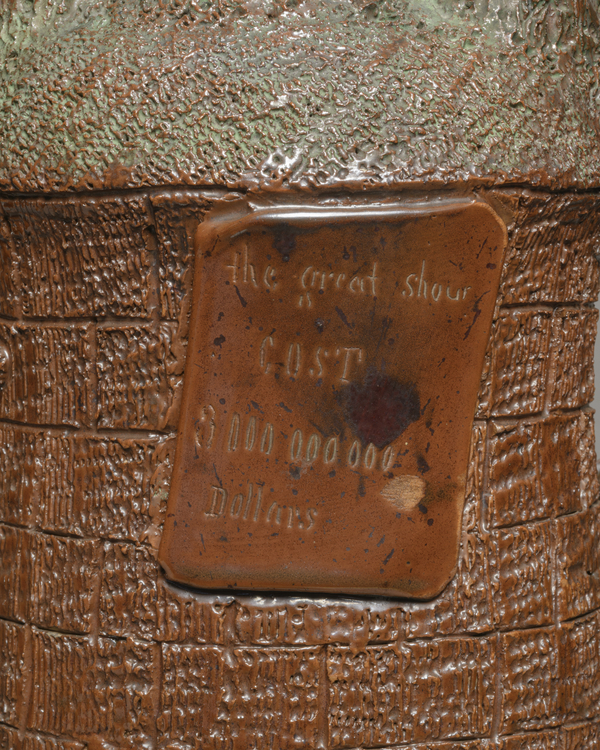

The large plaque on this side of the tower reading “the great show / COST / 3 000 000 000 / Dollars,” referring to the Civil War, suggests the Kirkpatricks considered the War to be expensive, theatrical, and ineffective in leading to a truly free nation.

How does the Monument criticize government corruption?

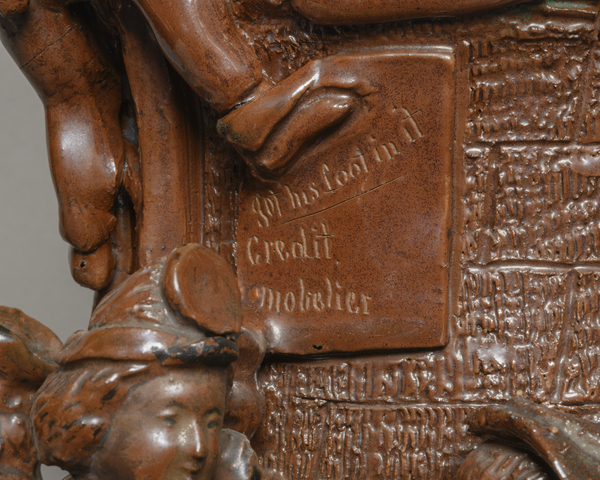

To strengthen the impact of their condemnation of the Colfax Massacre, the Kirkpatricks portrayed Schuyler Colfax, vice president (1869–73) under Ulysses Grant, with “Colfax” written on his leg. Though not associated with the tragedy in Louisiana, Colfax epitomized government corruption. He was implicated in the infamous Crédit Mobilier scandal over the Union Pacific Railroad’s gross overcharging for building its portion of the Transcontinental Railroad. Here, Colfax teeters atop a ladder near the inscription “this great / hight makes / me dizzy.” His foot rests on a plaque that reads “got his foot in it / Credit Mobelier.” Below, well-dressed white people stand near the words “my friends are falling.”